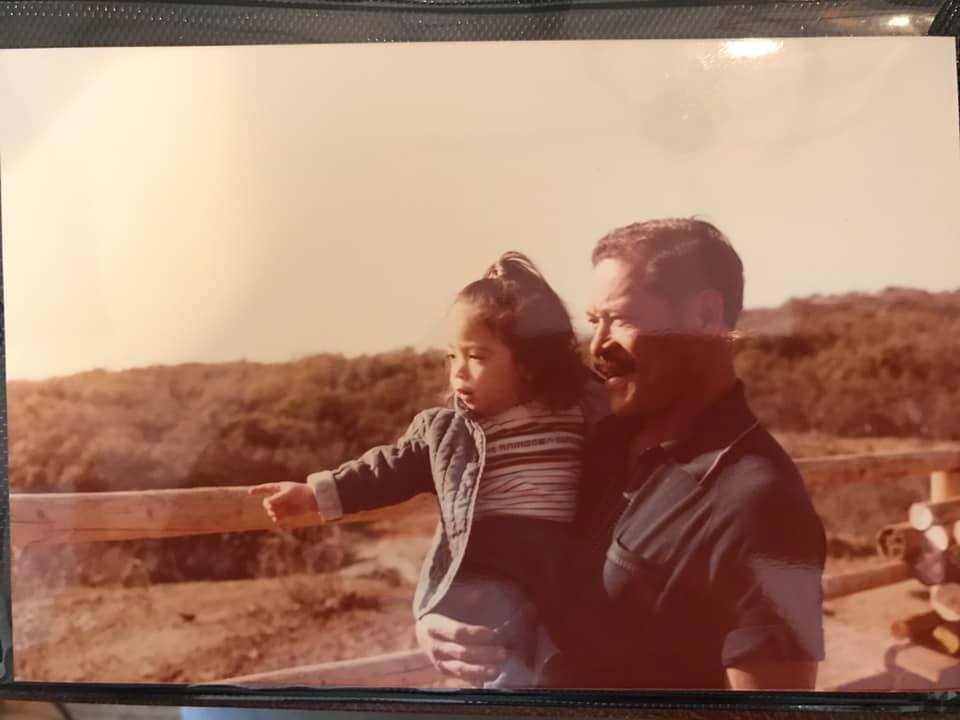

This is a painful topic to visit, but I think perhaps it is time to bring it out into the open. For as long as I can remember, I have never felt “good enough.” Perfectionism. Impostor syndrome. Depression. Anxiety. Overachiever. That wound by any other name still hurts. A lot. I’ve thought wryly that I’m even an overachiever at feeling not good enough — the mantra “I am good enough,” for example, is not at all soothing or affirming for me. In truth, it grates on me. I don’t want to be just good enough, I want to be the best. At everything. To everyone. The favorite. The winner. Perfect.

Introspection and a couple really excellent therapists have made me wonder if I actually want to be those things, or if I feel like I need to be them. It is, of course, the latter. And yet, how do I let this need go? We could start with logic, perhaps:

- Perfection is impossible.

- I cannot be the best at everything.

- I cannot be everyone’s favorite person.

And to try to be or do any of these is not only impossible, it is exhausting. I have set myself up to fail (which is somehow also one of my greatest fears — failure. Being a perfectionist is hard, y’all!). Not everyone will even like me. And that’s okay.

Unfortunately, though, logic is rarely as helpful as we want it to be when confronting one’s demons. I don’t yet have all the answers to healing this core wound, but bringing it into the light is a good first step. I am lucky enough to have wonderful, loving people in my life to reassure me when I need it, and sometimes when I don’t, which is so beautiful. Cognizance and kindness are two things buoying me as well: awareness of these woundings, and the gentleness I can offer myself when they arise. And while I walk this road to healing, the immortal words of Mary Oliver are ever a comfort. I hope they can be for you as well.

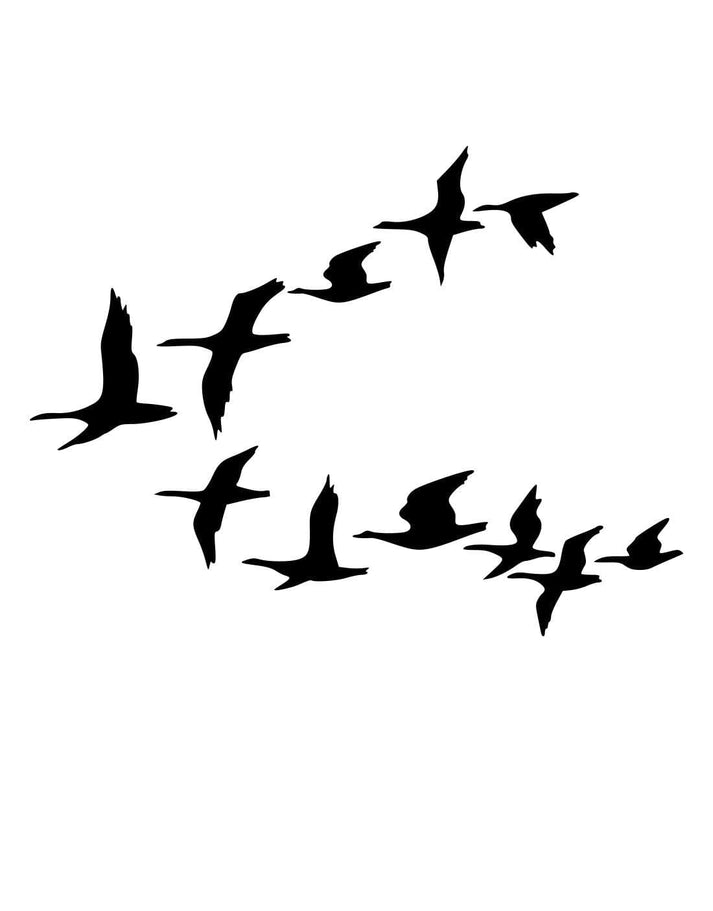

WILD GEESE

by Mary Oliver

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting –

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.